Umberto Dominico Ferrari, a retired bureaucrat who can’t survive on his meager pension and is about to be evicted from his room by an unsympathetic landlady. He reaches out unsuccessfully to former colleagues for help but as the film progresses we realize that Umberto’s only real emotional connections in the world are with his dog Flike and with Maria, a pregnant and uneducated maid who is as lonely and desperate for help as he is.

Umberto D. is the film that best expresses De Sica’s humanism. While De Sica overtly shows Umberto’s flaws, we still identify with him. De Sica portrays Umberto without being sentimental. We know little about Umberto’s life and his past, we are engaged Umberto today, in his seventies, approaching the end of his life and carrying with him the burden of his present and past struggles. This has made him into an irritable old man. But he is also capable of kindness. For example when he shows compassion towards Maria and her condition as a poor, single and pregnant woman. He encourages her to study “some things happen because you don’t know your grammar. Everybody takes advantage of the ignorant.” Yet when his beloved pet is lost, he blames and yells at Maria, who has just been deserted by her baby’s father, for the loss of his dog.

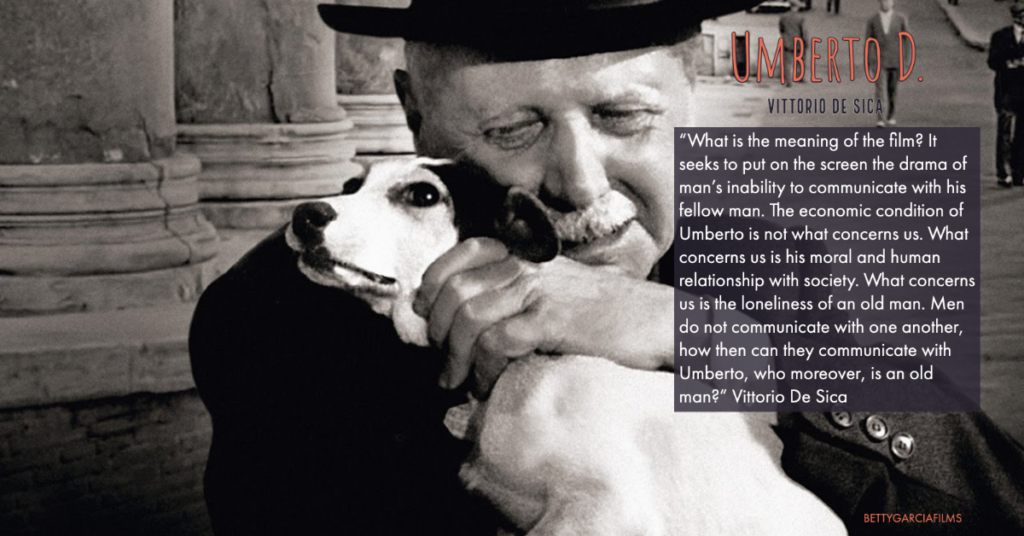

Although at the time of its release, Umberto D. was a commercial failure and the subject of bitter critical opposition, it has since been regarded as a masterpiece. To me, Umberto D. remains the best of De Sica’s films and the one that constitutes a purer and more refined application of Cesar Zavattini’s neorealism theoretical precepts. After their collaboration in the poetic realist film Miracolo a Milano (Miracle in Milan, 1951), De Sica and Zavattini returned to neorealism with Umberto D., a film which resists conceding to commercial demand and any form of traditional film spectacle. Of all of his films, it was De Sica’s favorite and he dedicated it to his father, Umberto De Sica, who was an impoverished bank clerk.

Umberto D. is the film that I prefer among all those I have made because in it I have tried to be completely uncompromising in portraying characters and incidents that are genuine and true…I have sought with great humility to approach the true, poetic, and limpid style of the great Robert Flaherty.

Vittorio De Sica

Umberto D’s story, like De Sica’s other neorealist classic, Ladri di Biciclette, is simple, beautifully told, and understated. Both films were inspired by the filmmakers’ passion to create a truthful and concrete representation of reality. However, in Ladri di Biciclette, the narrative is more traditional, while Umberto D.’s story tends more towards a ‘slice of life’ plot. These slices of life are set within the framework of traditional narrative, but the film is in no way driven by structure. If one assumes some distance from the story and can still see in it a dramatic patterning, some general development in character, a single general trend in its component events, this is only after the fact.

For this film, Zavattini and De Sica chose a subject matter with little audience appeal: the day-to-day trials of an elderly pensioner, and defied the public to identify, or even to empathize with Umberto, who they portray as a selfish and irritable old man. They construct a narrative made up of ordinary events loosely connected around Umberto’s moral and human relationship to society, and they dwell on these events with beautiful simplicity, revealing the most intimate details of the character’s actions. This intimacy is far more revealing of the reality of a character than any confessional dialogue or intense dramatic exchange. A great illustration of this unique approach to narrative and direction is the scene of Maria, the maid, getting up and going to the kitchen to start her day. The camera gently follows her as she does her daily chores. De Sica and Zavattini divide this scene into smaller events showing every detail of Maria’s activity. For example, we see her shut the kitchen cabinet door with her outstretched foot as she grinds the coffee. In this sublime scene, which lasts approximately 4 minutes, there is a complete respect for actual time and duration.

Here’s the trailer for Umberto D. with brief introduction by me.